When Camie Walker chose an Engineering Adventures activity for her fifth-grade classroom two years ago, she was thinking about how the lessons would complement her plans for English Language Arts instruction. She never expected that the real-world engineering design challenge would help her students become more resilient in the face of failure . . . or move them to meaningful social action on behalf of a young boy left destitute by a natural disaster.

When Camie Walker chose an Engineering Adventures activity for her fifth-grade classroom two years ago, she was thinking about how the lessons would complement her plans for English Language Arts instruction. She never expected that the real-world engineering design challenge would help her students become more resilient in the face of failure . . . or move them to meaningful social action on behalf of a young boy left destitute by a natural disaster.

What Happens in Haiti Also Happens in CA

Walker teaches at John Murdy Elementary, a school of about 400 students in Garden Grove, CA. It’s in a neighborhood called “Little Saigon” that is home to many Vietnamese-American families. Back in 2014, knowing that California had adopted the Next Generation Science Standards (which integrate engineering with K–12 science), she started looking for engineering activities to try in her classroom.

An online search led her to Engineering Adventures, EiE’s out-of-school-time curriculum, where the unit Shake Things Up: Engineering Earthquake-Resistant Buildings caught her eye. “My students were studying earth science. Living in California, what better topic to explore than earthquakes!?” she says.

Engineering is Like “Common Core 101”

Another attraction was how the lessons supported Walker’s goals for ELA instruction. “With Common Core rolling in, we were being asked to focus on critical thinking, collaboration, and problem solving,” she says. “Well, what does engineering do? It’s Common Core 101! You start with a question, do research, and work to solve a problem. It was a great fit.”

Another attraction was how the lessons supported Walker’s goals for ELA instruction. “With Common Core rolling in, we were being asked to focus on critical thinking, collaboration, and problem solving,” she says. “Well, what does engineering do? It’s Common Core 101! You start with a question, do research, and work to solve a problem. It was a great fit.”

The massive earthquake that hit Haiti in 2010 provides the real-world context for the design challenge in the Shake Things Up unit—and launched students on a problem-solving mission. When Walker asked students to compare the Haiti quake to an earthquake of similar magnitude that struck southern California around the same time, the exercise led to lots of questions.

“Here, the damage to buildings was small and twenty-five people died,” Walker says. “When the kids researched Haiti and learned that four hundred and fifty thousand people perished—and many kids their age were orphaned—there was shocked silence in the room. Then my students started to wonder, ‘Why? Why such different outcomes in California and Haiti?’”

If at First You Don’t Succeed, Go to Plan B

After an in-depth exploration of building codes, it was time for students to engineer their own earthquake-resistant buildings. Walker invited students to use “found materials” for their constructions. “They brought in everything you could think of, including mud and adobe--because that’s what buildings are made from in Haiti!” she says. “But on the day we did the ‘shake test,’ every single model failed miserably.”

After an in-depth exploration of building codes, it was time for students to engineer their own earthquake-resistant buildings. Walker invited students to use “found materials” for their constructions. “They brought in everything you could think of, including mud and adobe--because that’s what buildings are made from in Haiti!” she says. “But on the day we did the ‘shake test,’ every single model failed miserably.”

This moment, Walker says, was when she discovered the power of engineering. “Ordinarily when my students fail a test, kids are crying,” she says. “But this time, they were like, ‘OK, Plan A didn’t work. Let’s go to Plan B.’ They weren’t looking to me to solve things. They were looking to each other. They truly become engineers.”

Taking Engineering Home

Walker had planned to end the unit after the first shake test. “I thought the students could just revise their designs on paper,” she says. But without any prompting, many students went home and redesigned their buildings, working with their families. “A full sixty percent of my kids are ELL students, and I had been looking for ways to connect with their parents,” Walker says. “This was an unexpected and powerful way to make that happen!”

Walker had planned to end the unit after the first shake test. “I thought the students could just revise their designs on paper,” she says. But without any prompting, many students went home and redesigned their buildings, working with their families. “A full sixty percent of my kids are ELL students, and I had been looking for ways to connect with their parents,” Walker says. “This was an unexpected and powerful way to make that happen!”

Redesigns completed, kids brought their constructions to school for another test. “My husband used the instructions in the EiE manual to make us a giant shake table, so we could put an entire Haitian community to the test all at once!” Walker says. “And in the end, all of the redesigns passed!”

Reaching Out to Help

Duprene’s mother was severely injured in the earthquake and could no longer work, but because Duprene and his siblings were not orphans, they weren’t eligible for aid. So this young boy, the same age as Walker’s students, was making bracelets and selling them on the street to earn money for food. “He was the sole support for his mom and siblings,” Walker says.Meanwhile, the initial research project had sparked students to ask how they could help kids who were affected by the Haiti earthquake. Through a friend, Walker connected with a nonprofit called Hope for Haiti. “That’s how we came to support a young man named Duprene,” she says. “He was eleven when the earthquake hit; he’s now fifteen.”

Duprene’s mother was severely injured in the earthquake and could no longer work, but because Duprene and his siblings were not orphans, they weren’t eligible for aid. So this young boy, the same age as Walker’s students, was making bracelets and selling them on the street to earn money for food. “He was the sole support for his mom and siblings,” Walker says.Meanwhile, the initial research project had sparked students to ask how they could help kids who were affected by the Haiti earthquake. Through a friend, Walker connected with a nonprofit called Hope for Haiti. “That’s how we came to support a young man named Duprene,” she says. “He was eleven when the earthquake hit; he’s now fifteen.”

Time for Another Plan B

Walker’s 36 students got together and decided they would all buy bracelets from Duprene. “But when I checked with the nonprofit, they said this plan would create a hardship for him,” Walker says. “How could he make so many all at once? How could he get them to us? So I went back to the students and said, ‘Sorry, great idea, but we can’t do it.’”

Walker’s 36 students got together and decided they would all buy bracelets from Duprene. “But when I checked with the nonprofit, they said this plan would create a hardship for him,” Walker says. “How could he make so many all at once? How could he get them to us? So I went back to the students and said, ‘Sorry, great idea, but we can’t do it.’”

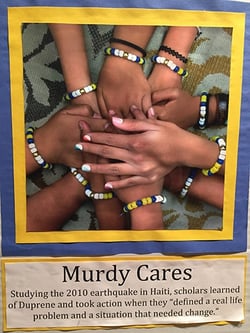

That’s when Walker’s students once again became problem-solving engineers. “They said “What’s Plan B?” Walker says. “And then they said, ‘Let’s make bracelets and sell them!”

Walker made a trip to a craft store for yellow and blue beads—the school colors. The students made bracelets during their lunch breaks, and also flyers to publicize their campaign. “When they told me they planned to charge ten dollars a bracelet, I though no one would buy them,” Walker says.

“But these kids had passion! They went around to all the other classes to promote the project and made almost two thousand dollars in two weeks.” Hope for Haiti got the funds to Duprene, along with letters from his new friends.

Kids Learn to Think of Others

That wasn’t the end of the story, though. The next year, at Halloween, Walker’s kids collected their candy and sent it, via the foundation, to kids in Haiti. At Christmas, they collected and sent stuffed animals.

That wasn’t the end of the story, though. The next year, at Halloween, Walker’s kids collected their candy and sent it, via the foundation, to kids in Haiti. At Christmas, they collected and sent stuffed animals.

“Hope for Haiti send back pictures of the kids getting their candy and stuffed animals, and my kids could see that what they did really made a difference,” Walker says. “This engineering activity pushed them out of being so egocentric and allowed them to care about other people and other places. Engineering challenges in international settings are the foundation of EiE units, and that framework allowed my students to make global connections.”

Getting to Be Part of the Team

Walker says the bracelet project also had particular impact on one boy in her class, a new student who, as an African American among mostly Vietnamese American students, was having a hard time making friends and fitting in.

“This activity really touched his heartstrings,” Walker says. “I noticed he was skipping lunch because he wanted to work on the bracelets, and I told him he had to eat. He said, ‘Mrs. Walker, how can I eat if Duprene is hungry?’" In the end, Walker says, working with his classmates on the bracelet project helped this boy feel like part of the team.

All in all, says Walker, “this was a powerful and amazing experience. The Engineering Adventures curriculum changed the way I teach . . . and the way my students learn.”