A few years ago, Baltimore educators and researchers launched an innovative STEM program for elementary students. One goal was to get parents engaged in their students’ STEM learning; another was to connect STEM learning to real-world issues in the local community. This focus on local connections is how Engineering Adventures, the out-of-school-time curriculum developed by Engineering is Elementary, came to be part of the “STEM Achievement in Baltimore Elementary Schools” project—SABES for short.

| Watch a short video about the SABES project |

Engaging the Community in STEM Education

|

The five-year initiative, a collaboration between researchers at Johns Hopkins University and the Baltimore City Public Schools, is funded by the National Science Foundation (DUE-1237992). SABES launched in 2013, targeting students in grades 3–5 at nine elementary schools in three Baltimore neighborhoods.

Plenty of programs share the goal of exposing kids to STEM subjects and STEM mentors at an early age; what sets this project apart is its emphasis on community engagement—a comprehensive plan that extends beyond school to parents and local organizations.

“We wanted to help parents be more aware of what STEM is and how they can engage their student in STEM learning at home,” says Alisha Sparks, the elementary STEM program manager. “We also chose to implement SABES in communities that could provide additional support for the program—for example, where there are strong community development corporations.”

And knowing that most people who grow up to be engineers had a role model or mentor early in life, SABES invites community volunteers to get involved. Professors from Johns Hopkins and local STEM professionals help out in the afterschool programs.

Going on Afterschool Engineering Adventures

|

| The EiE Engineering Design Process for grades 1–5 |

How does it all fit together? During the school day, kids get enhanced science and engineering instruction; teachers use curriculum materials developed by SABES, including mini engineering challenges based on the EiE Engineering Design Process. Schools also partner with community out-of-school-time programs to offer afterschool enrichment; that’s when students get to go on an EiE Engineering Adventure.

“We chose Engineering Adventures for the engaging stories that frame each engineering challenge, for how these stories feature children the same age as our students, and for how each unit focuses on developing solutions for real-world, global problems,” Sparks says.

For example, third graders become mechanical engineers in order to address an ecological issue, designing humane traps to catch a harmful invasive species. Fifth graders become structural engineers as they learn about the earthquake that wracked Haiti in 2010 and design model buildings to be quake-proof.

“Later in the year, students draw on what they’ve learned as we transition to student-driven projects,” Sparks says. “We start with a community walkthrough to get ideas. At one school, students noticed that many kids were straining to carry heavy backpacks and decided to explore designing a robotic backpack to prevent back injuries.” Another group, responding to train wrecks that had been in the news, brainstormed technologies that could alert train engineers when people are in the area.

Framing Failure as a Positive Experience

|

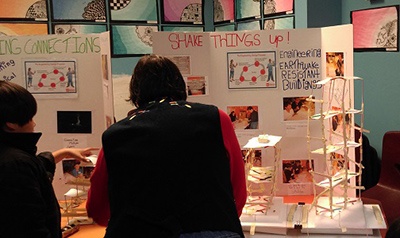

| Model buildings from the EA unit Shake Things Up on display at a SABES STEM Showcase |

Bernard Royster, the technology teacher at SABES school Rognell Elementary, works with the afterschool program and say, the way engineering frames failure as a learning experience really benefits students. “When we did the EA Earthquakes unit, one student created a building that wasn’t well designed—she only used index cards, not some of the sturdier materials available,” he says. “And it didn’t survive the shake test. This is a student who doesn’t like things not working!”

A Hopkins mentor worked with the frustrated student, asking simply, “What can you do to make your project better?” “The student started asking her own questions,” Royster says, “like, ‘What is stronger, a pipe cleaner or a popsicle sticks?’ She rebuilt her structure, and it passed the test. She had such a sense of accomplishment and self-assurance!”

Sparks says beyond the positive impacts for students, Engineering Adventures is a great fit for SABES because of the scaffolding it provides for afterschool facilitators. “Not everyone is used to teaching STEM subjects,” she says. “The curriculum does a good job laying out how to walk students through the engineering design process, and what to expect at each step. Educators who go through the curriculum guide can feel confident they’ll be able to engineer with their students.”

Families Learning STEM Together

|

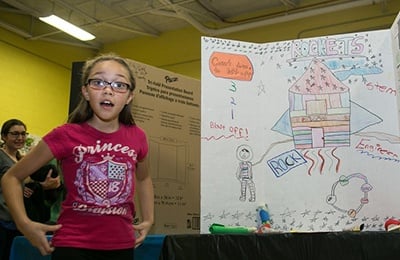

| A student presents her work on the EA “Liftoff: Rockets and Rovers” design challenge. |

STEM Showcases are held twice a year, giving family and community members a chance to see student-driven projects and students a chance to practice their presentation skills. Students and their families also get the opportunity to experience and learn STEM together through interactive demonstrations by organizations like the Maryland Science Center and Global Air Media.

“The parents are very supportive and attendance at the showcase has been outstanding,” Royster says. “It’s like a rainbow in the sky to see the joy, and how proud and appreciative they are that their children are having this opportunity.”

What Success Looks Like

More than 80 percent of City Schools students are from low-income families and about 85 percent are African-American—two demographic groups that are underserved in STEM education programs and underrepresented in STEM careers. The project will monitor outcomes including performance on a fifth-grade standardized test; the researchers expect students who participate in SABES will show not only increased academic performance but increased interest and motivation; they also expect that children whose experience with SABES includes the afterschool program will show greater interest and motivation than children who participate in the in-school program alone.

SABES is now in its fifth year; when the program wraps up, it will have reached over 125 teachers and more than 3,000 grade 3–5 students. “Ultimately, the project seeks to create a community-wide culture of STEM learning,” says Sparks, “where STEM is relevant to everyone’s lives, in ways that spark parents and other caregivers to sustain their student’s curiosity outside of the classroom.”

“In the past, when we asked students, 'What do you want to be when you grow up?’ we rarely heard, 'I want to be an engineer,'" Royster says. “When I’m in the classroom now and see how engaged the students are, to me, that’s a positive sign. If we can crack open the door to engineering careers, these students can push through.”

Engineering is Elementary is a project of the National Center for Technological Literacy® at the Museum of Science, Boston.